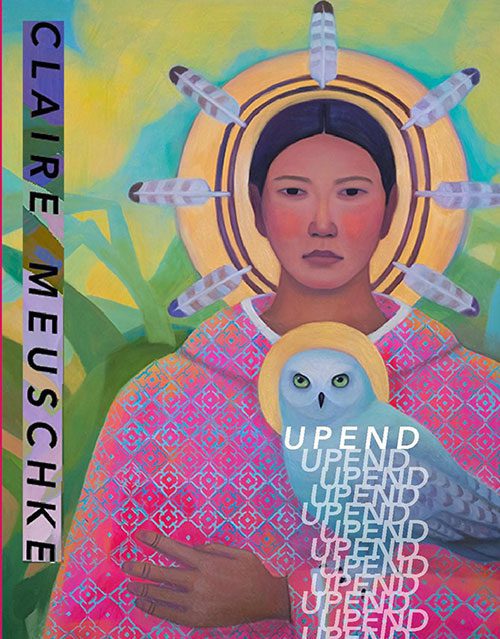

UPEND

by Claire Hong

$9.99 – $18.00

Synopsis

The book loosely navigates the archived immigration trial of Hong On, a biracial Alaska Native-Chinese man, in 1912 on Angel Island, CA during the Chinese Exclusion Act. Hong On was born in San Francisco, CA in 1895 and was orphaned shortly after. The concepts of U.S. government-designated recreational spaces, genocide, and intergenerational trauma are examined by Hong On’s granddaughter, the author, who sees imperialistic residue in product, place, and color naming. At the core of this book is the speaker’s Alaska Native great grandmother who is named “Unknown: Indian” on Hong On’s birth certificate.

Blurbs

Claire Meuschke takes us back to the immigration trial of her grandfather Hong On, more than a century ago. The violent, racially motivated forces behind US colonialism burn through these poems, showing how Manifest Destiny has resulted in a people and land still vibrating with trauma. “what about immobilizing guilt / organized resistance / the land not wanting you?” Here is a poet doing the real work to examine not only where we have been, but how to save ourselves from further destruction. This is a book I want everyone to put inside our lives, and to do so right now!

CAConrad

UPEND is a call to action, a living archive, a mirror of our shared public and private HIStories, a conjuration of ancestral lineages, the unknowns and the unearthed, a summoning the hypocrisy of codification and a continuous glimpse of the violence and residue that ripples throughout geographies, family lineages and into our present day. Upend is a riveting poetic journey of scholarship, retrieval and speaking truth to power.

Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle

On August 2, 1912, a man named Hong On was interrogated by US Immigration officials on Angel Island, CA. 100 years later, his granddaughter, Claire Meuschke, discovered the transcript of her grandfather’s interrogation. One of the results of that discovery is Upend—a book that exists in and cultivates the ongoing aftermath of an ancestor’s subjection; mends the spaces of distress, by re-embodying them, through the perpetual rooting and uprooting—disembodiment—of the present; and reimagines—upends—the fraught order of inheritance, therefore the orientation of poetry: that what we are given, and what we make with what we are given, we give back: to the past.

Brandon Shimoda